New Releases Movies

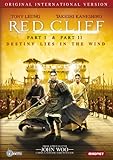

Red Cliff International Version – Part I & Part II

-

Movies News6 years ago

Movies News6 years agoVenom struggle scene footage with out CGI is sure to make you giggle

-

Movies News4 years ago

Movies News4 years ago‘The Eyes of Tammy Faye,’ ‘The Card Counter’ Revive Indie

-

Movies News4 years ago

Movies News4 years ago‘Shang-Chi’ Adds $21 Million as Box Office Slows Down

-

Movies News4 years ago

Movies News4 years ago‘The Many Saints of Newark’ Magical and Burdensome, Reviews

Stephen M. Kopian

September 30, 2010 at 4:27 am

Review by Stephen M. Kopian for Red Cliff International Version – Part I & Part II

Rating:

I’ve seen John Woo’s Red Cliff a couple of times now in both the full “international” version, which is really the way the film was made and the shorter International version which was shown in theaters and on pay per view here in the US. This version essentially removes over two hours of material from the story. (If I figured it correctly this version cuts the first half of the full version to an hour and the second half to about 80 minutes)

To me the full version is the way to go and not this theatrical release. The problem with this short version is that it removes a great deal of character development, numerous subplots (which makes several shots at the end of the film not mean anything-why is that soldier mourning a dead enemy? Its something thats been removed), the real ends of some characters and plots, and amazingly a great deal of the action sequences (the most obvious cuts are in the opening and closing battle sequences which are very cut down). In this case less is less.

Yes, the film moves faster (but I think more confusingly) and yes its removed many of the philosophical and strategic talks that some people found dull, but at the same time it makes the film little more than a series of connected battle scenes.The full version has a scope of action and character rarely equaled in film. This short version is pomp and circumstance with little behind it. I also find it confusing, which is strange since I had seen the full version twice prior to seeing this cut version.

To me the way to go is to see the full version. yes its five hours long but its on DVD where you can stop and pause. This version is considerably less than that full version, containing many of the visual highs but little of the emotional peaks.

Grady Harp

September 30, 2010 at 4:20 am

Review by Grady Harp for Red Cliff International Version – Part I & Part II

Rating:

John Woo has created the biggest budget epic yet to be produced in China. RED CLIFF (Chi Bi) is a monumentally grand film, distilling portions of the novel of Chinese history, ‘Romance of the Three Kindgoms’ by Guanzhong Luo, to recreate the famous battle in 180 AD between the north of China lead by evil Cao Cao (Prime minister in the Han Dynasty) and the south of China represented by the gentle and wise Liu Bei. The historic battle took place on land and especially on water as the huge forces from the north traveled the Yangtze River to the pass called the Red Cliffs (Chi Bi) where the southern forces gathered and came into ultimate confrontation.

The story is told both by voice over (in English) and by the actors – a cast that includes such highly regarded actors as Tony Leong, Takeshi Kneshiro, Fengyi Zhang, Chen Cang, Wei Zhao among others. The interpersonal relationships are well constructed but the real thrill of this film is the choreography of the battle scenes. The cinematography by Li Zhang and Yue Lü is splendid: the views of China’s landscape are breathtakingly beautiful. The costumes BY Tim Yip are complex and are apparently authentic in rendering the period. The only disappointment is the musical score by Tarô Iwashiro which sounds too Western to fully enhance the visual epic before the viewers eyes. The pacing is such that the greater than 2 1/2 hours of the film seem to fly by (apparently this is a condensation of parts I and II released in China). John Woo knows how to manage spectacle but he also understands the importance of emphasizing the human interactions that prepare the viewer for the explosive climaxes. Grady Harp, January 10

Josef Bush

September 30, 2010 at 3:49 am

Review by Josef Bush for Red Cliff International Version – Part I & Part II

Rating:

After watching the entirety of it, one thinks, ‘It is as if Sun Tzu had written it: This is a kind of illustration of what he meant when he wrote in his ART OF WAR [500 BC]’ — “All warfare is based on deception. Hence, when able to attack, we must seem unable, when using our forces, we must seem inactive; when we are near, we must make the enemy believe that we are away; when far away, we must make him believe we are near. Hold out baits to entice the enemy. Feign disorder, and cush him.”

When you deal in superlatives it’s difficult to make good comparisons. How many of us have seen BIRTH OF A NATION in a good print? That was the film that set the standard for sweeping battlefield drama interwoven with the stories of its participants, moving in scale from intimacy to immensity, back and forth as the story developped, fulfilled itself, then ended. Ridley Scott’s KINGDOM OF HEAVEN, with its portraits of historical figures interwoven within the threads of political and religious frenzy as Jerusalem falls to the armies of Saladin. I’ve seen many films of historical battles, and these two, RED CLIFF and KINGDOM OF HEAVEN, are the only ones that reach BIRTH OF A NATION’s high mark. In recent years we’ve seen TROY and ALEXANDER, and although both have been noble attempts to reach and to justify the scale appropriate to their historical subjects, neither effort managed to fulfill the expectation.

The Casting of RED CLIFF is brilliant. The many thousands of performers, from the battlefield extras and foot-soldiers, to the supporting roles, and even to the leading characters in the story, they all express and in a way never before seen, not only the ancient hegemony of China, but the enormous diversity of human appearance that hegemony must express. It’s similar to the realization that steals upon one after looking at the thousands of figures of the ancient Han army unearthed only decades ago; that these statues are portraits of individuals, that that terra-cotta army is the largest extant exhibition of portrait sculpture in the world. It is a demonstration of overwhelming power and technique. And somehow, the producers of RED CLIFF have managed to re-create that feeling. The logistics of costuming, and arming such a large cast boggles the mind.

The Director, John Woo, we all know because of the number of very successful commercial Hollywood films he’s made. We know that he was born, raised and educated in the USA, and in his TV interviews (on this DVD too) we find ourselves before a man of awestome accomplishments, who’s confidence is expressed by his modesty.

The movie stars two remarkable young actors: They are TONY LEUNG as Viceroy Zhou Yu, and TAKESHI KANESHIRO, who plays Zhu-Ge Liang, diplomat and military advisor. LEUNG I’ve seen in several movies, and most recently in the remarkable HERO, with Jet-Li, and what has impressed me most about him is his ability to change his appearance and manner so prodoundly, that he appears to be able to reshape himself physically, so that one can hardly recognize him from one film to another. Here, in RED CLIFF, I was uncertain who he was until the second time I watched the film, he did a short bit of practice with his sword and I recognized him by the movement of his body. He has a way of moving as he handles his weapon, that is unique to himself; a combinatin of sinuosity and strength that reminds one of a flexing steel cable. In RED CLIFF he is clean-shaven and handsome in a straightforward, almost military way, whereas in HERO he wore a van Dyque, his hair was loose, and his face wore an expression that made him look like was listening to sad music. Very unusual! KANESHIRO, I first saw in HOUSE OF FLYING DAGGERS, playing the role of a young police detective and philandering playboy. Tall, willowy and an excellent swordsman, he is light on his feet and wears a face that charms as it thinks.

These two actors and their personal characteristics are crucial to the telling of the story because it is a story that depends on a successful alliance between two states in their effort to save themselves before an advancing enemy with power to overwhelm them both. It is a question of Persuasion, that asks, how does one persuade an intelligent, sensitive and commanding individual to join with oneself and one’s few allies, in an effort to overcome a ruthless, clever and well-provisioned man who intends to conquer and overwhelm everything and everyone before him? How does one find the means to inspire not only trust, but confidence that together one can win in the face of overwhelming odds? This is not a tennis match. This is a matter of life, and/or a very unpleasant death, not only for oneself, but for one’s family and clan.

Woo directs this episode with a deep understanding of what is needed to forge a friendship between two proud and independent men, that is more than a superficial alliance of necessity. This is the psychological key to the inevitable conflict. Yang meets Yin, but will they join?

The final section of Part I of RED CLIFF, features the lead up to a battle scene that is worked out partly, on a 3-dimensional model of the batlefield, where Zhu-Ge Liang places a live turtle. Nobody understands, but he is recommending a method of defeating a large, heavily armed colum of Cavalry, and we get to see it worked out in the battle itself. A carefully trained corps of Infantrymen with highly-polished shields, pikes and swords, by close-positioning their sheids into walls and assuming a series of enclosed formations, force the advancing horsemen to ride between those formations through the continually narrowing and blinding alleys those formations make. The strategy is based mostly on the predictable behavior of frightened horses. The streams of horses speed up as the alleys narrow. WHen the alleys turn, abruptly, the horses must follow, because startled, they can see no way out, only one way forward. The riders are picked off by the infantrymen, from behind, and killed as they are dragged inside the shields. In no time at all the Cavalry force is consumed within the formation of shields, which from above and in perspective resembles a turtle’s carapace.

PART TWO shows us how the war is fought by means of knowledge of the weathr, about how to trick your opponhent into giving you his arms without knowing that he is doing so, and how to let your enemy cripple himself by thinking he is punishing traitors when he is only elimiating dupes.

Much of this part has to do with intelligent spying, by infiltrating the ehemies ranks, and about the use of instant communications; here, it means the use of carrier pidgeons.

And of suprememe importance; it has to do with understanding the weather; the movement of the winds and clouds. The defenders of RED BLUFF want to use fire against the blockade of ships filling the river before then, and the stockade straddling the river, beyond then, but hesitate because the wind will blow the fire back at them. BLOWBACK, literally. But Zhu-Ge Liang has reasoned that the wind will change because he has been watching the clouds and testing the humidity, and he has come to believe that the seasonal wind will reverse itself at about 01:00 AM.

And here something is revealed that astonished me. As Zhu-Ge looks up at the sky, we see an unusual form of cumulous (rain-bearing) couds streaking or hurtling across the sky. It looks like a kind of smoke pot being pulled across the heavens, trailing a body and tail behind itself. And instantly you remember that the Dragon is a rain-bearing spirit that appears regularly, and seasonally, and is a manifestation of goodness (or luck) and masculinity (or fecundity) causing seed to germinate. With his motion-picture camera, John Woo offers us a unique filmed portrait of China’s Dragon. So, what we see is what Chinese people have always seen, and artists for thousands of years have attempted to draw; that is, a coiling, feathery cloud-serpent skittering across the sky.

Nevertheless, battle plans are set. All forces are in formation. There is a water-clock, and we watch the minutes pass, drop by drop.

Much else is happening. The Viceroy’s beautiful wife, Chiling Lin has left their home in order to go to their adversary and to plead for an end to the war. Does she know that he is and has been her secret admirer since the time he first saw her while visiting her father? Perhaps. What is her weapon?

On board the enamy’s command vessle, the would-be conqueror prepares to enjoy possessing the Viceroy’s wife.

Our spy, the King’s sister, has escaped the forces of their opponents and throwing off her man’s disguise, reveals her knowledge in the form of a painted cloth wound around her body, which turns out to be a detailed map of the enemy’s fortifications and navy.

As the enemy commander welcoms the wife of his adversary on board his ship, once in possession of her quarters she begins to prepare tea, and invites her host/captor to have some. He accdepts.

The winds reverse and flags display it. The fire-boats are launched from RED CLIFF and one-by-one they crash into the enemy navy’s wooden ships. The battle begun on the water, moves to the land as allies of the RED CLIFF comrades return to fight with them against their common enemy.

The battle is joined, in earnest, and I don’t think there is any conflagration on film to compare with it; not even the burning of Atlanta. Ive never seen any acting-out of warfare more complex, more detailed than this. The scale of it is incredible. Battle scene buffs and advocates of all stripe will want to watch this, and will come away with something to satisfy themselves, I feel sure.

Finally, in a sentence or two, this film of John Woo’s is unlike many if not most of the Chinese historical films we’ve seen for the past few years, if only because he does not rely on lore or fantasy or fantastical effects to carry his story forward. Instead, he uses standard cinematic practice, as any of the big-screen American directors might have used it in their Westerns. Every shot, every episode is built solidly upon every shot and episode before it, until the progress of the action — as astonishing as it often is — appears as inevitable as nature herself might have made it. Nothing is obscure. One leaves the experience satisfied, not puzzled. We understand all the characters, all the situations. Everybody, everywhere in the world, will watch, enjoy and praise this film, because it is universal in its story-telling power, and thrilling in the display of its immense cinematic competence.

Catherine L. Chen

September 30, 2010 at 3:04 am

Review by Catherine L. Chen for Red Cliff International Version – Part I & Part II

Rating:

Throughout the centuries, every Chinese schoolboy is familiar with the stories from Luo Guanzhong’s Romance of The Three kingdoms. And those who cannot read listen intently to the tales of battles and wily stratagems recounted by storytellers in the market place or on stage performed by traveling troops of regional operas. The moment, Cao Cao, the villain, with a white painted face steps on stage, he is booed. However, when Liu Bei of Shu, the hero, and his sworn brothers, Zhang Fei and Guan Yu, and Zhuge Liang, and appear, cheers are heard. Often, after a particular favorite incident is recited, the storyteller says, “that’s enough now; come back tomorrow.” And then, the young and the old linger a little longer in case the storyteller has changed his mind.

In his Asian blockbuster movie that is presently in the theaters of southern California, Red Cliff, the modern storyteller, John Woo, recounts the same historical tale, the battle of the Red Cliff in 208 CE, taken place toward the end of a long and illustrious dynasty, the Han Dynasty, but with a new twist and perspective from that of the traditional ones. He is the grand master of storytellers with the help of cinematography, great actors, and visceral depiction of action that has dance- like qualities.

Red Cliff begins with Cao Cao, the prime minister of the last emperor of Han dynasty, a brilliant ruler, strategist, and warrior having asserted his rule over northern China. Cao Cao is confident that his military campaign of 800,000 men can subjugate the two kingdoms of Wu and Shu in the south. These two kingdoms jointly have a military force of 50,000 men. It is another story of mythical proportion like that of David and Goliath. Whereas Cao Cao schemes to usurp the Mandate of Heaven from the Han dynasty to establish a new dynasty, Wu and Shu are determined to stop Cao Cao’s lust for power.

John Woo’s epic focuses on the psychological and military battles fought between Cao Cao and Chancellor Zhuge Liang of Shu, and Viceroy Zhou Yun of Wu, the military commander-in-chief of Sun Quan. The climax of the movie is when the sky is set afire by the burning of Cao Cao’s flotilla on the river by the Red Cliff. The winners of this Chinese chess game are the heroes of a new age.

There are a number of high points in Red Cliff. Among which are the bagua battle array, stratagems of collecting 100, 000 arrows and anticipating a favorable wind to destroy Cao Cao’s flotilla by Zhuge Liang, and tricking Cao Cao to execute his two maritime commanders by Zhou Yun.

Unlike traditional portrayal of heroes and villains of the battle of Red Cliff, which lacked depth and complexity, John Woo’s main characters are multi-faceted. For example, Cao Cao is not merely a villain with a white painted face. Woo’s Cao Cao does have a heart as hard as a stone as he sends the boats carrying the infected dead across the river to the camp of the heroes. And yet, he is genuinely empathetic to his own weary soldiers and he appreciates talents in others. He also has other fine qualities. Even though Cao Cao is full of courage and treachery at the same time, he is dominated by greed. His desire to possess Xiao Qiao, the wife of Zhou Yun, becomes his downfall. During a moment of tea appreciation, Xiao Qiao points out to Cao Cao that when a cup is filled too full, it overflows. Cao Cao’s ambition leads him to great ventures and heights and when it turns into excessive greed, he is left with nothing.

John Woo’s heroes, Zhuge Liang and Zhou Yun, are larger than life because of their virtues and compassion for the laobai xing, the common man. When I ask John Woo who is his favorite character in Red Cliff, he replies, “Zhou Yun is my favorite character because he has a strong sense of values. He is upright, he believes in friendship, he is a family man, and he cares for those around him. I feel that movies today lack role models like him.” And indeed Zhou Yun is portrayed as the good overcoming evil during one of the bloodiest periods in Chinese history when seventy percent of the population was decimated.

John Woo has created in his characters an element of the Chinese tragic, which is different from the Western concept of the tragic. In the West, it is pride that causes the hero who is larger than life to fall. In the Chinese tradition, one of the tragic elements is the inherent conflict between love and duty. In Red Cliff, each heroic character whether man or woman is confronted by this conflict. This Chinese tragic element has added much conflict and tension to the movie. Otherwise, the movie is simply a painting of a dragon without eyes. And the eyes of John Woo’s dragon burn with passion and power.

by the author of The Flight of the Wild Cranes, Catherine Li