Kevin Winter/Getty Images

When you think of pop music, who do you think of?

Katy Perry, Lady Gaga, Ariana Grande, Britney Spears, Rihanna, Taylor Swift , Fifth Harmony—the list goes on. All extremely famous female faces, all women whose biggest hits to date have men’s fingerprints all over them.

Not that there’s anything wrong with those men, or at least most of them, but it’s a reminder that the music world—like so many worlds—is still dominated by men behind the scenes, be it in the studios, the editing booths or the conference rooms.

Only 10 women were included on Billboard‘s 2016 Power 100 list, none in the top 10, and only five of them didn’t share a spot with at least one man. There are also no women on the list that you’ve ever heard of if you aren’t particularly familiar with corporate rosters.

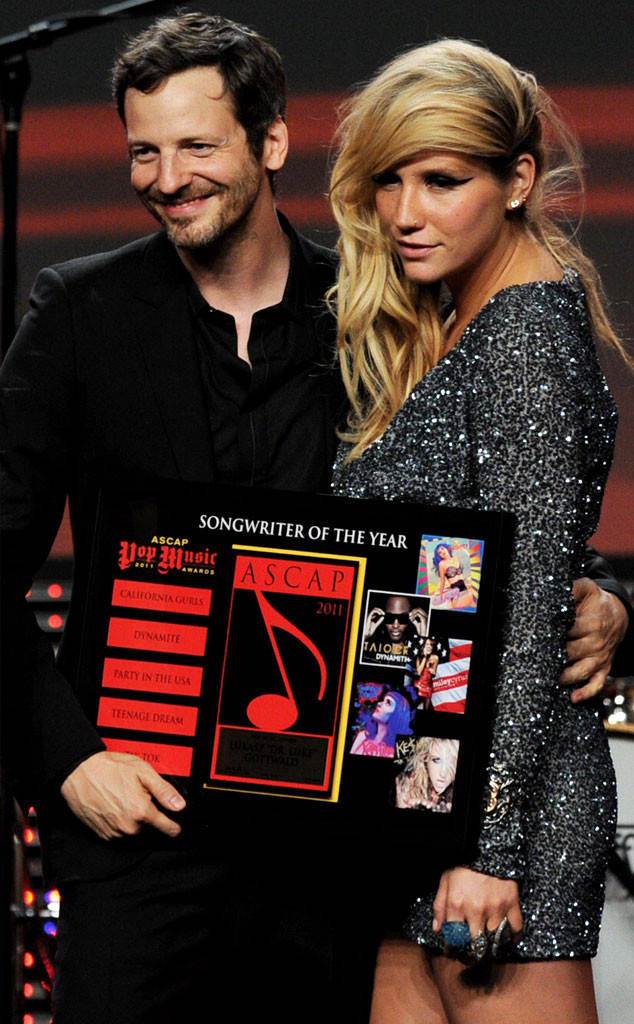

And so the latest dagger flung in the ongoing battle between Kesha and producer-songwriter Dr. Luke is a reminder that pop music remains a man’s world that some women, no matter how famous, are just singing in. The “TiK ToK” singer has accused the hit-maker (whose real name is Lukasz Gottwald) of sexual assault and emotional abuse over the course of a now years-long legal fight to extricate herself from a contract with Sony Music, home of Dr. Luke’s Kemosabe Records.

Gottwald has vigorously denied Kesha’s allegations, claiming in a counter-file that she conjured those accusations to get out of her contract, which she signed in 2005 not long after Gottwald heard her demo and brought her out to Los Angeles to record. He has twice sued the artist and her mother for defamation.

Kevin Winter/Getty Images

Last summer Kesha filed to dismiss the sex assault allegations but she remains stuck in her Sony deal, with the entertainment behemoth maintaining that she’s legally required to fulfill her end of the deal but doesn’t have to work with Gottwald.

So the battle continues, and this past week came the filing of court documents that included transcripts of emails purportedly sent by Gottwald to Kesha’s manager, Monica Cornia, in which he expressed concern she wasn’t sticking to a diet plan, writing, “the A list songwriters and producers are reluctant to give Kesha their songs because of her weight.”

Cornia defended Kesha, saying she was working very hard, to which Gottwald replied, per the court filing obtained by E! News, “Nobody was calling anybody out. We were having a discussion on how she can be more disciplined with her diet. There have been many times we have all witnessed her breaking her diet plan. This particular time it happened to be Diet Coke and turkey while on an all juice fast. We just want to see her stick to the plan for her benefit and the benefit of her career. Please help keep her on her diet. No need to respond any further.”

In another exchange, Gottwald allegedly fired back, when Kesha suggested an alternate lyric for “Crazy Kids”: “I don’t give a s–t what you want. If you were smart you would go in and sing it.”

Dr. Luke’s attorney, Christine Lepera, told Rolling Stone the release of the correspondence was a cherry-picked attempt on Kesha and her attorneys’ part to “mislead” the court and public opinion—and that the emails were evidence of “the tremendous support that Dr. Luke provided Kesha regarding artistic and personal issues, including Kesha’s own concerns over her weight.”

Whether that exchange was plucked out of context or not, it’s hard to believe those emails are the only ones of their kind, either between Gottwald and Kesha’s camp or the singer herself, or between other concerned parties in the music business pertaining to a female artist’s appearance or her creative input.

Aside from the fact that it could have been lifted from a 1955 memo from a studio head regarding the latest up-and-coming starlet, a memo surely dictated to a female stenographer, who then typed it out accordingly, it’s a discomforting glimpse at not only how much appearance still plays into the overall package (that’s hardly surprising), but that it’s still the guys dictating the terms of what a woman is supposed to look like.

Kelly Clarkson told Ellen DeGeneres in 2015 that her weight has been a hot topic since she was first on American Idol in 2002.

“I was the biggest girl in the show, too. And I wasn’t big, but people would call me big,” the platinum-selling singer said. “Because I was the biggest one on Idol and I’ve kind of always gotten that.”

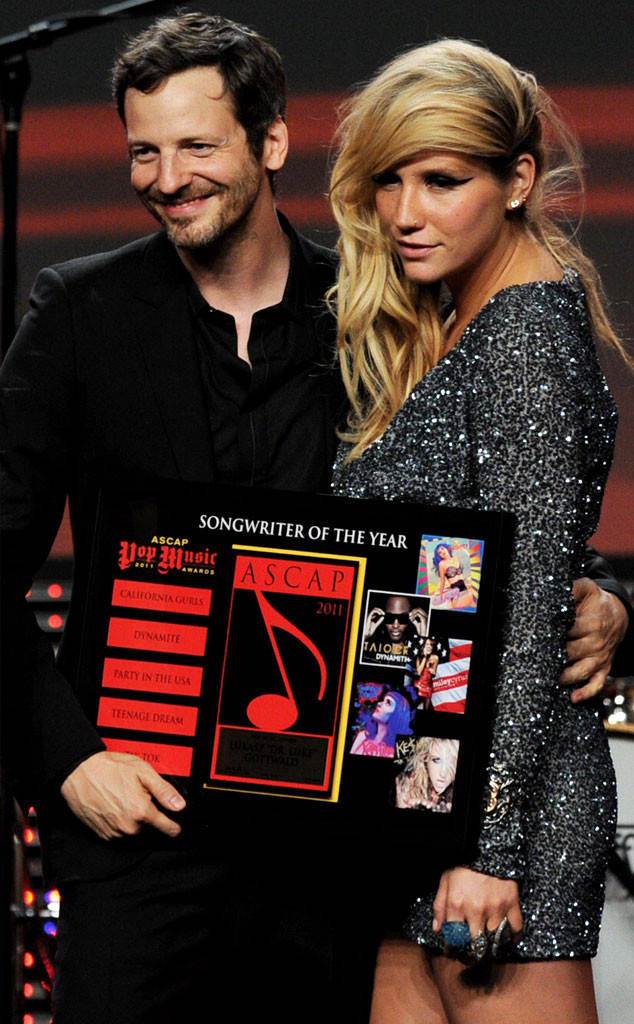

Last year, JoJo told Pop Sugar that her former label pressured her to shed pounds—and that she was hardly alone.

Jamie McCarthy/Getty Images

“I was under a lot of pressure with a company I was at previously and they wanted me to lose weight fast. So they got me with a nutritionist and had me, like, on all these supplements, and I was injecting myself. It makes your body only need certain calories, so I ate 500 calories a day,” the “Too Little Too Late” singer recalled.

She complied, knowing it was unhealthy, because, as she put it, “I felt like, ‘If I don’t do this, my album won’t come out.’ Which it didn’t! So it’s not like it even worked.”

There are of course women who have risen to a certain point where they take their cues from no one, least of all some male producer, but the likes of Madonna, Beyoncé and Lady Gaga are few and far between—and Gaga has opened up about having a hellish experience with a male producer 20 years her senior who sexually assaulted her when she was 19 and first starting out.

“I wasn’t even willing to admit that anything had even happened,” Gaga told Howard Stern in December 2014. “I saw him one time in a store, and I was paralyzed by fear.”

After the Stern interview, Kesha’s attorney Mark Geragos tweeted, “Guess who the rapists was [sic].”

Gottwald’s attorney and Gaga’s rep denied that Dr. Luke was whom she was talking about. But Gaga telling her story, after which she co-wrote and performed the Oscar-nominated “Til It Happens to You” from the documentary The Hunting Ground (about rape culture on college campuses), triggered a seismic shift on the pop culture landscape with regard to discussing sexual assault.

“I didn’t tell anyone for, I think, seven years,” Gaga said during a TimesTalk panel in December 2015. “I didn’t know how to think about it. I didn’t know how to accept it. I didn’t know how not to blame myself, or think it was my fault. It was something that really changed my life. It changed who I was completely.”

She added, “Because of the way that I dress, and the way that I’m provocative as a person, I thought that I had brought it on myself in some way. That it was my fault.”

No other artists have come forward with similar allegations against Dr. Luke—and he’s worked with the biggest, including Miley Cyrus, Katy Perry, Britney Spears, Pinkand Rihanna—but a parade of women, including Gaga, Taylor Swift and Adele, rallied around Kesha last year, on social media and beyond. Supporters toting signs imploring Sony to #FreeKesha gathered outside the label’s office in New York City last February in protest of a judge’s decision that there was no legal recourse to release her from her contract.

Kelly Clarkson told Australia’s KIIS 1065 last March that she was pretty much forced to work with Dr. Luke, who along with superstar Swede Max Martin produced “Since U Been Gone” and “Behind These Hazel Eyes.”

“He’s a talented dude, but he’s just lied a lot,” Clarkson said. “I’ve run into a couple really bad situations. Musically, it’s been really hard for me because he will just lie to people. It’s like, ‘What?’ It makes the artist look bad. He’s difficult to work with, kind of demeaning, it’s kind of unfortunate.

“People are like well you’ve worked with Max and Luke, and I’m like, ‘Max and Luke are very different.’ Obviously the dude is a talented guy but character-wise, no.”

And while Kesha remains in legal limbo, her situation did spark a new conversation about the treatment of women in the music industry, shining a glaringly bright light on how male-dominated the business remains and the archaic treatment that women are still subjected to to this day.

“I don’t know enough about the specifics of that situation, because it seems very complicated,” electro-pop artist Grimes told Rolling Stone last April when asked her thoughts on Kesha and Dr. Luke. “But I will say that I’ve been in numerous situations where male producers would literally be like, ‘We won’t finish the song unless you come back to my hotel room.’

“If I was younger or in a more financially desperate situation, maybe I would have done that. I don’t think there are few female producers because women aren’t interested. It’s difficult for women to get in. It’s a pretty hostile environment.”

Dimitrios Kambouris/Getty Images

In 2015, Grimes called out the ingrained sexism in the music-making process, telling The New Yorker, “I can’t use an outside engineer. Because, if I use an engineer, then people start being, like, ‘Oh! That guy just did it all.'” The Canadian artist said, “It’s a mostly male perspective—you’re mostly hearing male voices run through female performers. I think some really good art comes of it, but it’s just, like, half the population is not really being heard.”

Chairlift frontwoman Caroline Polachek, who’s also a producer and songwriter who penned and produced Beyoncé’s “No Angel,” acknowledged a catch-22 for women who succeed behind the scenes in the business as well as behind the microphone.

“There are plenty of female artists out there now who are self-produced and doing cutting-edge productions to surround their own vocals or compositions, which is vital part of the musical landscape right now, but the resulting message is that the female producer is an aesthetically presented vocalist who only produces her own songs,” Polachek told The Fader in 2014, not long after Kesha first sued Dr. Luke.

“This sets up three additional hurdles to an already challenging field, because vocal chops, aesthetic presentation, and songwriting are three separate and time-consuming skills that should in no way be prerequisite. The archetype of Male Producer (take Rick Rubin, or Phil Spector for example) is not a man who necessarily composes, sings, or looks good on camera. Quite the opposite—the Male Producer is passionate about music but not a performer, putting in years hunched behind the console in unglamorous isolation before achieving guru status. By holding up female performers as producer-icons, we could potentially be discouraging the girls who don’t feel comfortable presenting themselves as visual objects from entering the field.”

She concluded, “Ultimately the music has to speak for itself and make the biggest change. I really think it’s only a matter of time though. I’d give it five years max till we have a top 10 track made by a female producer.”

DJ-producer Jubilee also told The Fader, “I think there are a million reasons [why there aren’t more female producers] and it’s way deeper than the ‘boys club’ theory. I think a lot of professions are like this. Less doctors, less lawyers, less filmmakers, less directors whatever. I think it stems from society telling girls they should be wearing pink and playing with Barbies and cooking in an Easy Bake Oven.”

Talking about gender inequality in the music business, John Seabrook, author of The Song Machine: Inside the Hit Factory, told Vice’s Noisey that “it usually breaks down that the men tend to be the producers and the women tend to be the hook writers. So, you have men (producers) and women (topline writers) and the way the studio sessions are set up and run, the producers—the men—book the rooms and are usually paid by the hour by a label. Whereas the women—the hookline writers—are only paid based on whether or not their songs make the cut. Most songs do not get made into records. So all the time they spend in the studio working on songs that don’t get made into records, is basically time they’re not paid for. Whereas the men are always paid, whether or not the songs turn into records.”

Lester Cohen/WireImage

Seabrook said that mega-producers like Dr. Luke and Max Martin “seemed aware” of the gender issues in music when he spent time with them, “but then the Kesha stuff went down after I had my time with Dr. Luke and there was no follow up about that. A lot of it’s just about money…The only ethic that exists is: take what you can.”

As Polachek also said, ultimately at the end of the day the music business is a business, and no one is getting hired, much less getting the keys to the castle, if the talent isn’t there. But the stereotype of the Svengali producer was established decades ago, probably even before Phil Spector was churning out hits with his Wall of Sound and terrorizing artists, including his own wife Ronnie Spector, behind the scenes.

Kim Fowley, the notoriously predatory musician-producer who was instrumental in getting The Runawaystogether, allegedly raped teenage bassist Jackie Fox at a party in the 1970s.

“I didn’t know if anybody would have backed me,” Fox told Huffington Post’s Highline. “I knew I would be treated horribly by the police—that I was going to be the one that ended up on trial more than Kim. I carried this sense of shame and of thinking it was somehow my fault for decades.”

About the Runaways’ persona that Fowley put together, guitarist Lita Ford told HuffPo, “He could be a jackass, but I understood what he was doing and what he was trying to tell everybody in his own Kim Fowley sort of way. He wanted us to be hot. He wanted us to have attitude and charisma.”

The Highline piece noted that Fowley, who died in 2015, was quoted in a 2013 band biography as saying, “They can talk about it until the cows come home but, in my mind, I didn’t make love to anybody in the Runaways nor did they make love to me.”

Fox talked to Highline in the wake of the explosion of sexual assault allegations against Bill Cosbyas well as after Kesha filed suit against Dr. Luke.

“They have to be making the same value judgments about themselves as I made about me,” she said, referring to fellow victims of rape. “I know from personal experience how all those things can eat away at you. They can take vibrant young people and turn them into something else.”

Sadly, the days of accepting (or, more accurately, ignoring) physical assault as “normal,” or part of “business as usual” or “playing the game” may not be over; furthermore, it’s starting to become apparent that certain ceilings are made of a material that’s tougher to break than glass.

Billboard

“What I really want to say is that it is really hard sometimes for women in music. It’s like a f–king boys club that we just can’t get into,” Gaga told a crowd that erupted into applause while being honored as Billboard‘s Woman of the Year in December 2015.

“I tried for so long, I just really wanted to be taken seriously as a musician for my intelligence more than my body ever in this business…You don’t always feel like when you’re working that people believe that you have musical background, that you understand what you’re doing because you’re a female.”

Gaga added, “Tonight is so important because women provide a wisdom to music that is very unique and special. It is a perspective that no other person can have because we bear life. And we go through things that no one goes through and more importantly because it’s right because we’re all equal.”

Kevin Winter/Getty Images

A fellow banger of the drum for female equality has been Ariana Grande, who has become a reliably outspoken critic of rampant sexism wherever it’s found—on social media, in the regular media, in music and beyond. The 23-year-old has plenty of personal experience with the subject, too, since wanting things her way has already earned her the uber-sexist label of “difficult.” (She also was among the artists who tweeted her support for Kesha.)

“I’ll never be able to swallow the fact that people feel the need to attach a successful woman to a man when they say her name,” the Dangerous Woman artist told Billboard last year. “I saw a headline—draw your own conclusions [on who it was] because it’ll be so much drama that I don’t want—they called someone another someone’s ex, and that pissed me off. This person has had so many great records in the last year, and she hasn’t been dating him forever. Call her by her name!

“I hate that. Like, I’m fuming. Sorry…Don’t get me started on this s–t.”

While Kesha has alleged that pretty much the entirety of her professional career has been inextricably tangled up with what she has characterized as Dr. Luke’s mistreatment of her, she also dealt with the average sexist backlash against her biggest hits, such as “TiK ToK” and “Die Young,” for what sounded like her unbridled endorsement of drinking, partying and hooking up.

“You know, when I first came out [on the music scene], I was saying I want to even the playing field,” Kesha told The New York Times in October. She had started performing again, but was sitting on nearly two dozen songs that the litigation prevents her from officially releasing. “I’m a superfeminist. I am an ultra-till-the-day-I-die feminist, and I am allowed to do, and say, and participate in all the activities that men can do, and they get celebrated for it. And women get chastised for it.”

The singer is now more than four years removed from the release of her last studio album, Warrior. She’ll turn 30 on March 1, meaning it’s been almost 12 years since she met Dr. Luke.

“As you grow up and you grow awareness, some say ignorance is bliss, and in some ways, it is, but once you realize and you gain knowledge, it’s there, and you can’t deny it,” she also told the Times. “And now I’m very much aware of things that I wasn’t before, and it keeps me more accountable for my actions.”

Ema (2019) 16 | 1h 47min | Drama, Music, Romance | 22 October 2020 (Germany)

Summer of Soul (…Or, When the Revolution Could Not Be Televised) (2021) PG-13 | 1h 57min | Documentary, Music | 2 July 2021 (USA)

Christopher Plummer’s Best Roles, From ‘The Sound of Music’

Inside Oscar Shortlist Races in Music, Makeup and Visual

11 Highest-Grossing Music Biopics, From Tupac’s ‘All Eyez on

13 Best Movie Moments Featuring The Beatles Music

Venom struggle scene footage with out CGI is sure to make you giggle

‘The Eyes of Tammy Faye,’ ‘The Card Counter’ Revive Indie

‘Shang-Chi’ Adds $21 Million as Box Office Slows Down

‘The Many Saints of Newark’ Magical and Burdensome, Reviews